IMR 3031 Smokeless Powder (1lb & 8lb Containers)

$30.00

IMR 3031

A propellant with many uses, IMR 3031 has long been a favorite of 308 Match shooters using 168-grain match bullets. It is equally effective in small-capacity varmint cartridges from 223 Remington to 22-250 Remington, and it?s a great 30-30 Winchester powder

Product information

A medium burn speed propellant with many uses, IMR 3031 has long been a favorite of 308 Match shooters using 168-grain match bullets. It is equally effective in small-capacity varmint cartridges from 223 Remington to 22-250 Remington, and it’s a great 30-30 Winchester powder.

IMR recommends always consulting www.IMRReloading.com for the most accurate, up-to-date data.

MORE information about IMR 3031

In this age of fascination with DNA and tracing our ancestors, it’s fun to do it with gunpowder. In fact, with some you can trace not only the family tree of the powder, but also the various companies that produced it down through the years. IMR-3031 has been a stalwart in the gunpowder lineup since the 1930s, which is a good lifetime for anything, but it’s not showing its age and there is no sign it will be joining the “discontinueds” anytime soon. Good old “3031” is just too useful to let go.

The first edition of Cartridges of the World was published in 1965. It was a monumental effort by author Frank C. Barnes, and became a handloading cornerstone through the following decades. I can’t count the hours I spent poring over every entry, when I should have been studying something “important,” like trigonometry.

Frank Barnes, being a shooter, wanted to keep old rifles shooting so, along with the factory ballistics of each cartridge, he included loading data with modern powders. One impression I had then was just how many cartridges, new and old, black-powder and smokeless, could be loaded to respectable levels with just one powder: IMR-3031. Even when there was a better option – with 4895, say, or 4831 – Barnes often included a 3031 load as well.

A quick flip through the latest edition of Cartridges of the World 16th Edition indicates that while the number of cartridges has mushroomed, no equally versatile powder has come along to displace IMR-3031. Loads are still listed for many cartridges. In more than 50 years, it has lost none of its usefulness.

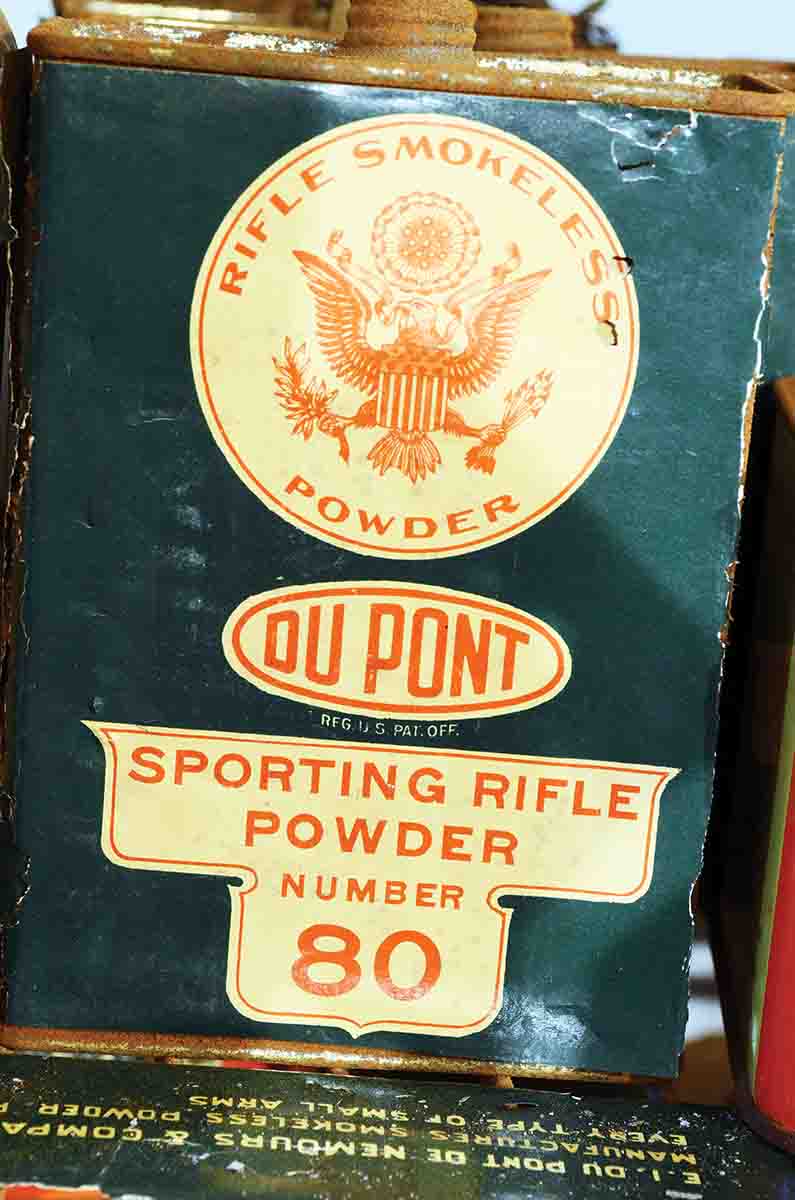

IMR-3031 was one of the illustrious family of “improved military rifle” powders introduced by DuPont in 1934-35, which also included IMR-4227, 4198, 4064 and 4320. In burning rate, IMR-3031 ranked in the middle, with 4227 and 4198 faster and 4064 and 4320 slower. These five became the core of DuPont’s line through the next 85 years and, in many ways, still are.

The five are all single-base powders extruded into small cylinders of varying length and diameter. Each was intended to replace existing powders in the DuPont lineup. IMR-3031 replaced a powder called DuPont 17½, which had been around since 1923.

Dupont 17½ was actually an older powder, DuPont 16, with tin added to the formula. The addition of tin was intended to reduce fouling from cupronickel jacketed bullets at high velocity, and while it did accomplish this, it also left gummy powder fouling.

Introduced in 1916, DuPont 16 became one of Philip Sharpe’s favorite powders for mid-sized cartridges. He describes it as DuPont’s “pride and joy” for many years – the “most flexible of the IMR series” and “adapted to more different sizes and shapes of cartridge and a wider range of velocities and burning pressures than anything previously produced.” It performed well, he wrote, at pressures from as low as 30,000 pounds per square inch (psi) all the way up to 55,000 psi. It could be used in cartridges from the .22 High Power through the .257 Roberts, .30-06 and .30-caliber magnums on up to the .405 Winchester.

Handloaders who had used it, he added, remembered its “extreme accuracy and tremendous velocities.” It was “long the author’s favorite powder.” He was not happy when it was replaced by the “dirty” 17½, and rejoiced when 17½ was dropped in favor of 3031.

These powders did not simply replace their predecessors. There was considerable overlap. Production of 16 continued until about 1927, while 17½ lasted from 1923 to 1933. There was also a DuPont 17 (1915 to 1925) that was a minor variation on 16 intended specifically for British military use. Because of the overlap, experimenters like Sharpe were able to directly compare the qualities of each powder in the same cartridges.

The benefits and negatives of each illustrate the problems facing ballisticians, powder companies and ammunition makers in the early years of the last century. Although technological progress continued at a dizzying rate, especially through the Great War, it seemed that each advance created a new problem, and each solution created new problems in turn. The cupronickel jackets that made high-velocity bullets possible created fouling; adding tin to the powder reduced this, but the tin created its own problem. In the end, gilding metal (copper/zinc alloy) jackets eliminated the need for tin in the powder, and DuPont could then concentrate on developing cleaner-burning powders.

Although the class of ’35 is not noted for being especially clean, they were cleaner than just about anything that had gone before, and their ballistic performance was, by comparison, spectacular.

.jpg)

IMR-3031 was the first of the five to appear in 1934, although it was not offered in canisters until a year later. Sharpe wrote that it was one of the cleanest-burning powders in the DuPont line, flexible enough to handle cartridges from the .22 Hi-Power up to the .405 Winchester, and delivering velocities equal to 17½ with much lower pressures. It was also cooler-burning, reducing bore erosion. He recounted experiments with “unsafe” loads that delivered spectacular accuracy – in one case a group of 10 shots with a 7×57 at 100 yards that could be covered by the head of the cartridge case. It was “the smallest 100-yard group the writer has ever seen.” Sharpe ended with the admonition: “Watch this powder.”

Over the years, Handloader has published three “Propellant Profiles” on IIMR 3031 , first by John Wooters in 1972, followed by Al Miller and, finally, R.H. VanDenburg. All spoke highly of it, in a wide variety of applications. Wooters called it ideal for competition loads in the 7.62mm NATO (.308 Winchester), and added that he liked it for stiff cast-bullet loads in mid-capacity cartridges like the .30-30 and .35 Remington. VanDenburg favored it for the .45-70 and said it “matched the velocity and exceeded the accuracy” of factory loads. Al Miller wrote that the most accurate loads in his .338 Winchester Magnum and .375 H&H used 3031, “and at no cost to velocity, either.” He summed up this way: “Reliable, clean-burning, accurate, and flexible, it’s the nearest thing to an all-around powder there is.”

Over the years, the powder has also been recommended as a smokeless starter for black-powder duplex loads, as well as a good “light” load powder in small quantities with Dacron fillers.

My most memorable use of IMR-3031 took place 20 years ago when I decided to test two rifles to destruction, noting the warning signs as the pressures mounted. One rifle was a P-17 .30-06 and the other was an 1896 Swedish Mauser 6.5×55. Aside from noting signs of increasing pressure, I also wanted to see whether, in fact, the 96 Mauser was weaker than the P-17 – a Mauser-98 derivative of noted strength.

I chose to work up loads with IMR-3031 because, with that powder, I could start with a legitimate published load and increase in a way that might well occur accidentally in normal handloading, witnessing the progression of signs as pressure increased. At the same time, I would not run out of case capacity before I reached terminal pressure. One might plausibly double-charge a 6.5×55 or .30-06 case accidentally, and this would show what could happen.

Surprisingly, everything went according to plan. Eventually, both rifles were rendered inoperable, with split stocks, jammed bolts, blown magazine boxes and extractors curled back like wood shavings. One cannot say the actions “failed,” because neither ever let go. The higher the pressures, the more tightly the bolts held until, ultimately, they would not open.

One thing I did prove was that while you might not be able to jam enough 4831 into a case to destroy a rifle, you certainly can with a medium-range powder like 3031. No writer has listed the possibility of destroying a rifle as one of 3031’s many desirable attributes, or as evidence of its versatility, so I offer that for what it’s worth. If nothing else, the experience made me vigilant to the point of mania.

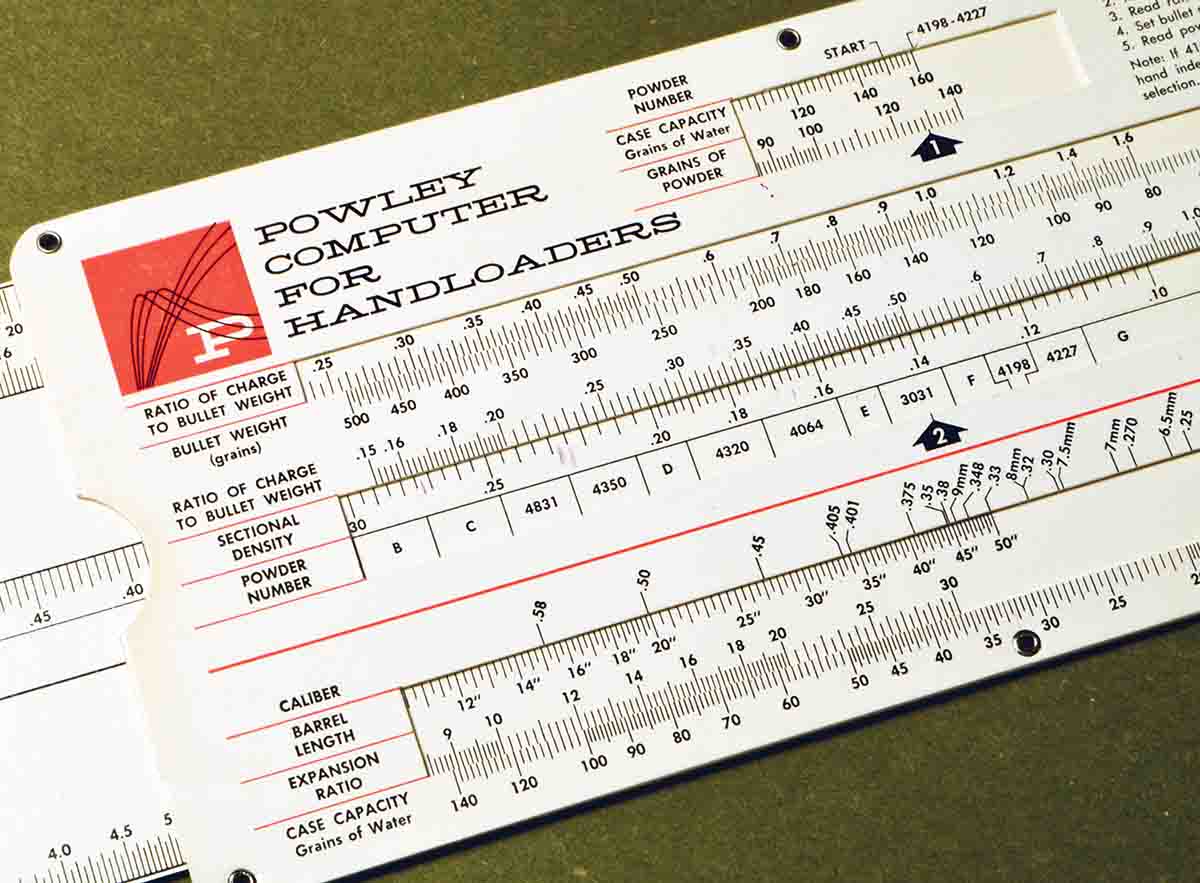

When ballistician Homer Powley created his slide-rule-like ballistic computer in the 1960s, the powders he used were the above IMR line from 1935, plus IMR-4350, Hodgdon’s H-4831 and the long-discontinued IMR – 5010. (For more on the Powley Computer, see Handloader No. 290, (June-July 2014). The Powley Computer for Handloaders was a cardboard slide rule that used case capacity, expansion ratio, and ratio of charge to bullet weight to compute the optimum powder and charge for a given combination of cartridge and bullet. It was available from 1963 to 1988, but was killed off by the personal computer and digital ballistics programs.

Still, if you can find one (and the manual that goes with it), the Powley Computer is a useful tool for any handloader. Unlike a digital computer, where you input information and it simply kicks a number back, you can follow the logic of determining a load, step-by-step, seeing how each factor affects it.

Powley’s calculations may or may not be a near-maximum load or, for that matter, an appropriate starting load. It pays to double-check against any published data you can find, and even then, it involves more than a little common sense based on experience.

Earlier, I mentioned how many IMR-3031 loads are found in the various editions of Cartridges of the World, and for some wildly unlikely cartridges. For example, in the first edition, there are loads for the .219 Zipper, .25-35, .280 Remington, 8×57, .358 Norma Magnum and .460 Weatherby; the 16th edition lists loads for the 6mm Creedmoor, .25-36 Marlin and 7.7mm Arisaka, among others. It’s worth noting, however, that some loads have been dropped. In the first editions, a load is given for the .450/.400 Nitro Express (3 inch), but by Cartridges of the World 16th Edition, that has been eliminated. This can probably be attributed to prudence.

This points up a highly-salient fact, not only about IMR-3031, but about many other powders in its class: They are among the most useful powders around, but because of their burning rate and the possibility of double-charging a case, they carry hazards as well. Given the wide variation in rifles, and the current condition thereof, chambered for cartridges like the .450/.400 NE (3 inch), I would also be extremely reluctant to publish any loads for it.

That brings us back to the Powley Computer. To use it, you need only combine an ability to measure case capacity, the native intelligence to apply some numbers, and the common sense to suspect when something is hazardous.

It’s interesting that, unlike 4350, 4831, 4198, and 4227, there is only one original IMR-3031. Try as I might, I could not find out why, given the universal agreement as to its virtues. Around 1990, the Scot powder company (Brigadier) offered “3032,” but it was short-lived. Maybe other companies thought 3031 was simply too good to compete with or, possibly, saw it as a midrange all-rounder in an age that demands highly-specialized powders.

Ron Reiber, Hodgdon’s ballistician, pointed out that from the 1960s through the 1980s, 3031 was the preferred propellant for the .308 Winchester with 168-grain match bullets.

“As time moved on, .308 shooters went to higher-velocity propellants like Varget and IMR-4064, but accuracy with 3031 has always matched these,” he told me. “Now, a top choice for the .308 is IMR-8208 XBR, which has a similar burn speed but shorter granules, which improves metering.”

Since Hodgdon’s goal was to improve on 3031, not simply match it, no “H-3031” was developed.

“Nonetheless,” Reiber added, “We still sell a lot of 3031, and quite a bit of it goes to other manufacturers for specialty loads. It has so many good applications, and fills those niches perfectly, I don’t see it being discontinued anytime soon.”

Be the first to review “IMR 3031 Smokeless Powder (1lb & 8lb Containers)” Cancel reply

Related products

Reloading Powders

Reloading Powders

.jpg)

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.